Cape Town: The Mother City Welcomes All

Cape Town: The Mother City Welcomes All

Cape Town, not content with rightfully claiming its spot in the pantheon of top-tier global travel destinations, is now emerging as a destination for Muslim travellers

At first, it’s the sky that captivates me: the afternoon’s luminous sunshine has given way to a veil of fog, and what should have been golden hour is instead aglow in silver.

Temperamental weather is par for the course during autumn in Cape Town, where sun and clouds regularly jostle for dominance throughout any given day. Having previously lived here I know this well, and yet I’m so preoccupied by the mercurial elements overhead that I almost don’t notice the sign before me: a placard that informs me I’ve arrived at Islam Hill.

Most visitors to Cape Town associate the posh suburb of Constantia with stately mansions and rolling vineyards. But I’ve come to this scenic valley at the southern tip of the African continent in search of something far different. As I step through the gate and pass stepped fountains ascending a gentle slope, I glimpse a green dome at the top of the hill, flanked by rows of towering cypress trees. This is the kramat, or shrine, of Sayed Mahmud, a religious leader from Indonesia who was exiled to Cape Town in 1667 by the Dutch. One of the first to bring Islam to the colonised Cape, his body now rests in this beautiful tomb, with softly lit mountains in the background evoking a dreamy watercolour painting.

I’d once lived at an address a mere 15 minutes away from Islam Hill and the kramat that crowns it, but somehow I’d never before been aware of its existence. The fountains flow past me with a soothing cadence as clouds churn dramatically overhead, and I stand still, soaking in the serenity with wonder.

“Now this is what I call a hidden gem,” says Latifa Cozyn as we retreat back to her car. As the founder of Cut Above Travel & Tours, Cozyn specialises in bespoke itineraries that take visitors to some of Cape Town’s most important Islamic historical landmarks – many of which are hidden in plain sight.

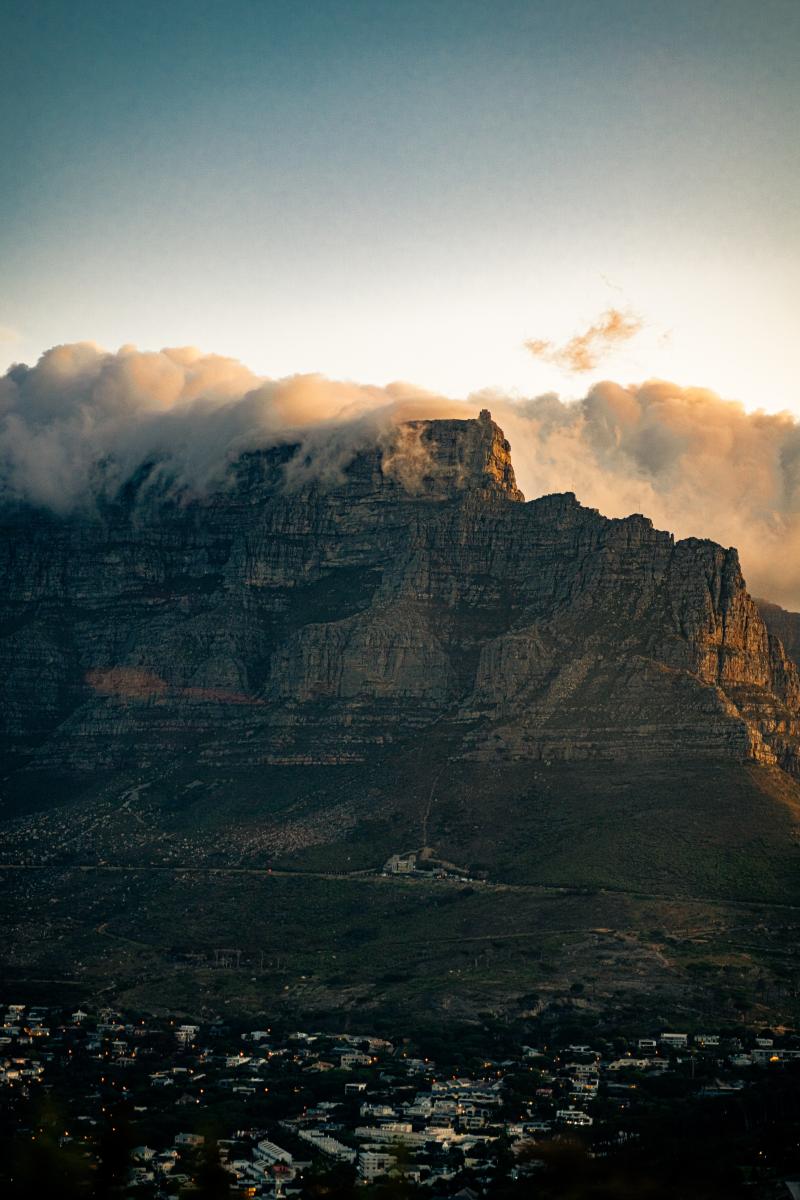

Muslim travellers to South Africa are often amazed by how accessible it is: malls and airports have salah facilities, and restaurants, from popular fast food chains and the tourist café at the top of Table Mountain to the city’s buzziest restaurants – like the vibey hotspot Ramenhead – are halal-friendly. Though they comprise less than 2% of the population, South Africa’s Muslim community is deeply woven into the fabric of the nation.

Simon's Town Table mountain (nature reserve)

in Cape Town

South African Penguin in Boulders Beach

But as respected as the faith is today, its origins in the Cape stem from hardship and tragedy: when the Dutch colonised South Africa in 1652, they brought the first Muslims to the region in shackles as slaves and exiles from Malaysia and Indonesia. South Africa’s modern colonial history is inextricably intertwined with Islam; even the first-ever written record of Afrikaans was in the Arabic script. The descendants of these early exiles from the east, many of whom were of royal or scholarly lineage, mixed with Africans, Europeans, Indians, and Arabs over the centuries, and the result is a vibrant, multicultural, and proudly Muslim community that exists nowhere else in the world: the Cape Malays.

On another misty morning, I set sail for Robben Island, the notorious prison where Nelson Mandela spent most of his 27-year sentence. But 300 years before he was condemned to the island, this is where many of the Malaysian and Indonesian prisoners were held after they were pried from their homes halfway across the world. A video playing on the ferry outlines the island’s long and harrowing history as a penal colony, and dedicates an entire segment to the various sheikhs and royals from the east who were imprisoned here. “Robben Island is an important crucible of Islam in the world,” the voiceover declares.

Our Robben Island guide, Craig van der Horst, is more blunt: “Islam was brought to South Africa as an enslaved religion,” he says. One sheikh, known as Tuan Guru, wrote five copies of the Qur’an by memory while he was imprisoned here, and after he was freed, went on to found South Africa’s first mosque and madrasa. His contemporary, Sheikh Sayed Abdurahman Motura, was said to have healing abilities by his fellow prisoners, and later died on the island.

When I walk up to the foreboding prison gates, my gaze is fixed on a simple structure just to its right; I’d noticed the domed mausoleum during my first visit a decade ago, but had no idea why this silhouette synonymous with Islamic architecture was in this bleak setting. Thousands of visitors to the prison pass by it without going in; today, with Latifa leading the way, I walk over to learn more. This is the kramat of Sayed Abdurahman Motura, a place so serene that, according to Latifa, Mandela himself used to come sit by it and reflect. “It’s a symbol of the struggle of Islam coming to South Africa, and a symbol of the survival of Muslims in South Africa,” she says.

There are more than 23 of these kramats forming a sacred ring around the Cape, many of them nestled in lively neighbourhoods and near major landmarks. The locations vary from a peak overlooking Oudekraal, on a scenic stretch of highway where Porsche and Mercedes commercials are regularly filmed, to the top of Signal Hill, and from the suburb of Macassar, named after a city in Indonesia, to the seaside hamlet of Simon’s Town, most fondly associated with its penguin colony on Boulders Beach. Local legend has it these shrines come together to forge a Circle of Islam, which shields the region from natural disasters.

“The old people would tell you we are protected by these kramats,” says Sheribeen Amlay, whose family runs the Heritage Museum in Amlay House, Simon’s Town. “That's why we don't have any calamities. We’re supposed to get hurricanes and tsunamis, and nothing has ever happened here.”

Just a short drive from Boulders Beach, a can’t-miss fixture on every Cape Town tourist’s itinerary, Amlay House is a treasure trove of memories. The Muslim Amlay family owned this elegant 150-year-old Victorian villa before they were forcibly removed by the apartheid government in the 1960s. After apartheid ended in 1994, Sheribeen’s aunt moved back in, and family members have filled every wall, surface, and room with artefacts and images painstakingly collected from Simon’s Town’s Muslim community. From the museum we stroll uphill to the charming Water Lane Mosque, which dates back to the early 1900s. “All these houses along here used to belong to us – this was the Cape Malay quarter.”

The better known Cape Malay quarter in Cape Town is one of South Africa’s most recognisable – and Instagrammable –enclaves. The rainbow-bright houses of Bo-Kaap are home to a thriving Muslim community, and tourists pause for requisite selfies in front of rowhouses in vibrant shades of fuchsia, violet, and marigold, interspersed with dozens of candy-coloured mosques. When I lived in Cape Town, I occasionally came to pray taraweeh during Ramadan at the Auwal Mosque, the oldest in South Africa, built in 1794. I pay a return visit during the quiet hours between Zuhr and Asr to take a look at one of the five Qur’ans written by Guru, which is immaculately preserved and displayed near the minbar. Afterwards, I head a few doors down to visit Fagmie Solomons, a local resident and former rugby star, in his turquoise home. “We’re a close-knit community in Bo-Kaap, that’s what makes us special,” he says. “There’s baraka in these houses.”

Back in Constantia, just outside the gates of the 17th-century Klein Constantia estate, I come upon an unexpected sight: yet another kramat, with autumn leaves swirling dramatically around its green dome and the scent of indigenous fynbos plants heady in the air. “Now you've seen the kramats of the first three Muslims who brought Islam to the Cape,” Latifa tells me as we walk towards the shrine of Sheikh Abdurrahman Matebe Shah, a Malaccan sultan who was exiled to South Africa in 1668. “Islam is peace, even though we come from slavery and oppression. They were exiled, enslaved, and tortured, but all of them had a purpose – they came to teach Islam. And in Islam, they found their freedom.”

As we walk towards the threshold, I hear a familiar sound and freeze. The melodious voices of two men reciting the 30th chapter of the Qur’an beside the grave drift out of the door and mingle with the chirping of the birds. While these kramats are an integral part of Cape Town’s rich Islamic past, this moment reminds me that they’re not mere relics of another era. Islam is also very much Cape Town’s present, a beautiful tapestry of faith and perseverance.

Where to stay

High above the colourful homes of Bo-Kaap, the Dorp is a jewel waiting to be discovered. Each of the 27 luxurious rooms are charmingly decorated with flamboyant old-world flair, and the windows frame spectacular views of Table Mountain. Dorp means “village” in Afrikaans, and true to its name this is more of a compound than a singular hotel, with courtyards and levels waiting to be discovered at each turn.

Every member of the staff – many coming from the surrounding Bo-Kaap neighbourhood – is engaging and warm, giving every interaction a personal touch. Don’t miss a traditional Cape Malay dinner at the popular Bo-Kaap Kombuis restaurant around the corner from the hotel; but be sure to hurry back for dessert. There’s perhaps no better perch on a winter evening than a well-worn couch by the fireplace in the airy lounge, where a slice of South Africa’s beloved milk tart is the perfect sweet ending to a day out in Cape Town.

dorp.co.za

What to do

Latifa Cozyn founded Cut Above Travel & Tours to focus on heritage tourism in Cape Town. She designs custom itineraries that encompass all the region’s highlights – city tours, Bo-Kaap visits, the Cape Peninsula drive, shark cage diving, and road trips throughout the Western Cape – as well as visits to the area’s various kramats and Islamic landmarks.

cutabovetours.co.za